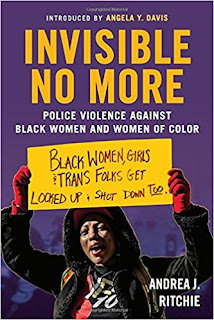

Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color—Andrea J. Ritchie

"In the end, the real challenge posed by women of color's experiences of police profiling and violence is to our collective conceptions of violence and safety, the role of police in our society, and to our ability and willingness to make building and nurturing values, visions, and practices that will produce genuine safety and security for all members of our communities a central task of movements against police violence." (239)I’ve talked about the LibraryThing Early Reviewers program before, and this is absolutely one of the top notch best ARCs that I have received through the program. I actually read this a few months ago, and am just now getting to write about it, so this book is now currently available for purchase.

I think this is probably one of the most important books

that I have ever read, and certainly one of the most important books I have

read in order to learn more about a subject that affects a population of which

I am not a member. The book looks at police violence against populations of

color, and then specifically through the lens of women of color.

Here’s the synopsis:

Amid growing awareness of police violence,

individual Black men—including Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Philando Castile,

and Freddie Gray—have been the focus of most media-driven narratives.

Yet Black women, Indigenous women, and

other women of color also face daily police violence. Invisible No More places the individual stories of women and girls

such as Sandra Bland, Dajerria Becton, Mya Hall, and Rekia Boyd into broader

contexts, centering women of color within conversations around the twin

epidemics of police violence and mass incarceration.

Invisible

No More also documents the evolution of a movement for justice for women of

color targeted by police that has been building for decades, largely in the

shadows of mainstream campaigns for racial justice and police accountability.

Informed by twenty years of

research and advocacy by Black lesbian immigrant and police misconduct attorney

Andrea Ritchie, this groundbreaking work demands a sea change in how police

violence is understood by mainstream media, policymakers, academics, and the

general public, as well as a radical rethinking of our visions of safety—and the

means we devote to achieving it.

Ritchie starts with a few introductory, more general

chapters, and then she separates the book based on specific communities within

the “women of color” population, taking a deeper dive into each. In each

section, she shares stories from and about women who experienced police

violence, looks at the history and background of the justice and political system,

the biased and ingrained racist beliefs that set the stage for this group to be

victims of police violence, and then recommends actions for “resistance.” These

subsections are: policing girls, policing disability, policing sexual violence,

policing the borders of gender, policing sex, policing motherhood, and policing

responses to violence. Because of this particular separation choice, she often uses

similar terminology and rhetoric, or refers back to concepts she mentions in

previous sections, so it can feel a tiny bit repetitive, but only because all

of these communities and stories are so interconnected.

Before I dig more into the content, I wanted to say that

overall, this book is incredibly well researched and sourced. It is a perfect

mix of academic, referenced writing, while still being accessible to someone

who doesn’t spend their life studying these stories. Which is really the

perfect mix, in my mind: explaining something in which you are an expert to

someone who is NOT an expert in a way that keeps them engaged and interested,

and potentially curious enough to look into other authors on the topic. That’s

the sweet spot. (I wish I didn’t feel the need to give gold stars for

referenced work, but after reading one too many nonfiction or research book

with basically zero references, those that are academically sourced stand in

stark contrast.)

Setting the Stage

There were a number of overarching takeaways for me. One was

really interrogating the role of police in society, which is not something I

had thought about quite so actively before reading the book. What role do

police currently play in our society, but also what role should they play? What

kind of situations should police have jurisdiction over, and which situations

might benefit from other community services first? And, barring anything else,

what kind of oversight of police discretion do we need to implement in order to

keep people safe.

Ritchie makes a point, both in this book and in interviews

and other pieces that I’ve read of her writing, to emphasize that we have to

look at the bigger picture of police patterns of behavior, and not only with

reference to fatal interactions. Many of the stories that she tells in this

book do not have a fatal ending, BUT they are no less important to consider

with regard to public safety and more specifically the health and safety of

women of color. And they also speak to an environment and ethos within police

departments that perpetuate and even support continuing violence against

historically marginalized communities.

Right off the bat, I appreciated Ritchie’s framework for the

conversation. She took the first several pages to discuss what this book is,

and perhaps more important, what the book is not, and WHY it’s not. She

explained that there would be a lack of focus on trans men and gender

non-conforming folks, and that her intention was not to erase, but to specifically

focus on Black women, women of color, and LGBTQ-identifying women.

One of the most important things that set the stage for the

content following was chapter 2, entitled “Enduring Legacies.” In it, Ritchie investigates

and lays out an historical timeline, showing a direct correlation between the

treatment of women of color in the past and the way they are treated today. Understanding

how slavery and colonialism were systemic instruments of repression, you can

see how little the rhetoric and conversation has changed on the national platform.

This is not an idea unique to Ritchie; more and more influential voices talking

about how the “war on drugs” and broken windows policing, among other policies,

have worked to prevent communities of color from succeeding. (For example, see The

New Jim Crow or 13th.) But

understanding it specifically within the context of police interactions with

women of color is imperative to understanding the remainder of the book.

Deeper Dive

In discussing the policing of poverty, Ritchie references

the war on drugs and so-called broken windows policing (sometimes called “quality

of life” policing). As she states, “Black women and women of color are

disproportionately impacted by the policing of poverty simply by virtue of

making up a significant proportion of the population of low-income and homeless

people of color.” (45) The same can be said for the “war on drugs”; as is true

across the board, people of color represent a greater proportion of those who

are incarcerated for drug offenses. “Black, Latinx, and Indigenous women make

up a grossly disproportionate share of women incarcerated for drug offenses,

even though whites are nearly five times as likely as Blacks to use marijuana

and three times as likely as Blacks to have used crack.” (47)

While mandatory minimums have led to judges often legally not able to show discretion in relation

to drug offenses, the enforcement of broken windows exemplifies the incredible discretionary power that

police forces have: “Police officers are afforded almost unlimited discretion

when determining who and what conduct is deemed disorderly or unlawful. More

specific regulations, such as those criminalizing sleeping, consuming food or

alcohol, or urinating in public spaces, criminalize activities so common they

can’t be enforced at all times against all people. As a result, both vague and

specific quality-of-life offenses are selectively enforced in particular

neighborhoods and communities, or against particular people…” (55)

Related to broken windows policing is the degree to which

young women of color are under scrutiny more than their white counterparts. The

zero tolerance policy in school is the educational equivalent of broken windows

policing. As with many situations, Black students and young women of color are

punished more severely for less serious incidents in schools every day.

One of the possible reasons behind this is a concept known

as age compression, or “adultification.” A recent

Slate article explains it, in relation to a recent

book and a Georgetown

study on the topic, but essentially it means that Black girls specifically

are often perceived as older than they are. From the Slate article: “Compared

to white girls of the same age, black girls are perceived as needing less

nurturing, comfort, and protection. They are also perceived as being more

independent and knowing more about sex and other adult topics. And the bias

begins early: Black girls are seen as older and less innocent than their white

peers starting as young as age 5.” Similarly, Latinx youth are often perceived

as “hot tempered” or “volatile” as a result of deeply ingrained prejudices and

biases, which adds its own measure of adultification and expectations.

In relation to disability, Ritchie puts forth a question that

could be asked at the end of all these situations: whether there are other

community services that might be better suited to provide assistance to crisis.

Though it’s not perfect, as it’s still run through the police department, she

cites a program called CAHOOTs in Eugene, Oregon, which has pioneered nonpolice

responses to mental health crises. Instead, a mobile crisis unit consisting of

a nurse or EMT and a crisis worker are dispatched in nonemergency police calls

relating to drug use, poverty, and mental health. As a result, CAHOOTs now provides

counseling instead of cops in a whopping 64 percent of calls. Is this solution

not something that could be expanded? Could it not be considered for other

situations? Is a police response the ONLY option?

Even if nothing else changes, the level of accountability

for police officers and the process for same HAS to change. All too often

throughout the book, Ritchie shares instances of officers FINALLY getting

punished for their crimes, only to find out that there had been a long history

of infractions and reprimands, yet these officers kept their jobs all that time.

How many injuries could have been prevented if cops were not just defending

each other blindly or covering up abuses? This is especially evidence in

chapter 6, which focuses on police sexual violence, and shows that not only do

women of color experience this to a higher degree than white women, but it is

even more prevalent for women who are trans, lesbian, or gender non-conforming.

This relates to chapter 7, policing the borders of gender.

Policing the borders of gender has a long, sordid history.

The policing of the borders of gender is also intricately tied up with the

policing of sex, as many trans women or gender non-conforming folks have often

been subject to accusations of prostitution merely as a result of their

appearance and of classification anxiety.

Across the board, women of color being demonized and

penalized for sex is nothing new but is definitely still a problem. The

enforcement of women who are considered loitering or soliciting in certain

areas is highly selective, and guess who it most often selects? This goes back

to the discretion allowed to police officers, who are enforcing vague “quality of

life” regulations. And, circling back to policing the borders of gender and

sexual police violence, police officers take advantage of this position of

power to blackmail women of color into sex. “A DC police sergeant admitted, ‘Everybody

messes over the prostitutes.’ Earlier studies by SWP found that up to 17 percent

of indoor and outdoor sex workers reported sexual harassment or violence by

police officers. In an analysis of three studies of a Midwestern city, 15.4

percent of women reported being forced to have sex with a police officer,

almost half (45.5 percent) had engaged in paid sex with police, and 18 percent

reported being extorted for free sex. Nationally, more than 25 percent of

respondents to 2015 US Transgender Survey who were or were perceived to be

involved in the sex trades were sexually assaulted by police, and an additional

14 percent reported extortion of sex in order to avoid arrest.” (156)

The policing of motherhood is closely tied to long-held

misconceptions and prejudices as well. Ritchie says, “In the 1980s the image of

the ‘welfare queen’ and ‘welfare mother’ has been added to the perceptions of

Black women rooted in slavery, joining in a toxic combination in which Black

motherhood and Black children represent a deviant and fraudulent burden on the

state that must be punished through heightened surveillance, sterilization,

regulation, and punishment by public officials.” (167) Black women and women of

color are often penalized for perceived threats to their children, and yet

there is no regard shown for mothers or expectant mothers when it comes to

interactions with the police. Latinx mothers are often subject to narratives

labeling their fetuses as immigration threats. In a number of cases of city

police and immigration enforcement, excessive and unnecessary force has led to

loss of pregnancy. Yet another case of rampant police discretion is present in

relation to the overseeing of child welfare. “Beyond responding to calls,

police are now also independently taking up child-welfare enforcement,

including in minor cases that would previously have been handled

administratively.” (178) These laws are also discretionarily used to a greater

percentage in relation to mothers of color. For example, Geraldine Jeffers. “She

was arrested and later convicted for child endangerment for leaving her four

younger children in the care of their fifteen-year-old sister when she had to

go to the hospital due to complications with her pregnancy and wound up being

admitted overnight.” (179) I’ve known white families who have left younger children

with a fifteen-year-old for lesser reasons and not been arrested for child

endangerment. At the end of this discussion of policing of motherhood, Ritchie

poses yet another important question: “Beyond organizing on behalf of Black

mothers and mothers of color, if we center their experiences, we begin to ask

new questions, including how should use-of-force policies address experiences of

pregnant women?” What would happen if we adopted “a public health rather than

punitive approach to drug use by pregnant and parenting women”?

Another huge aspect of this entire injustice is that women of

color do not feel that they can trust police to act in their own interests, and

especially when it comes to violence against them. We’ve already discussed

examples of how women of color and people on the edges of gender expression can

be victimized by police themselves, but there’s another aspect of not being

able to trust the police. Marissa Alexander shot into the air to stop an

assault by her husband, and she was charged with a felony, even though no one

was hurt or even in danger of being hurt as a result of her actions. Native

women are often disbelieved as the result of stereotypes focused on perceived

alcohol use. And it’s not surprising that more than half of respondents to the

2015 US National Transgender Survey said they would feel uncomfortable asking

police for help.

Reliance on police is exceptionally problematic for women who are

undocumented. This discussion was brought somewhat to the forefront with the

advent of this new presidency and the possible abolition of sanctuary cities.

All studies show that when people who are undocumented are afraid to talk to

the police, crime goes up. Distrust of police leads to greater community

turmoil and crime. But as we move further into this new era of hatred and fear,

those feelings of distrust and discomfort relying on police is likely to

worsen.

Once again, at the end of this chapter, Ritchie proposes

considering an alternative to police response: “Ultimately, the experiences

described in this chapter, along with countless others, counsel strongly in

favor of a critical examination of current approaches to violence against

women, and the development and support of alternative, community-based

accountability strategies that prioritize safety for survivors; community

responsibility for creating, enabling, and eliminating the climates that allow

violence to happen; and the transformation of private and public relations of

power.” (201)

What Needs to Change and How We Can Change It

Another of the overarching themes that stuck out, as you may have noticed throughout this review, is the incredibly amount of discretionary power that police have, with often little to no oversight or accountability.

A further common thread that emerged, along with the

overabundance of discretion for police officers, is the general inclination to

treat the women of color that they encounter as less than people. Whether this

manifests as shooting an unconscious 19-year-old woman 22 times, as was the

case with Tyisha Miller; or as a complete disregard for someone’s privacy by

dragging a quadriplegic woman out of her house half naked when she did not

comply with their commands to “get the fuck up,” as was the case with Lisa

Hayes; or as the use of the apparently completely legal search of a woman’s

vagina looking for drugs, as was the case with Shirley Rodriques. (There were

no drugs.)

It just so happens that I finished the book mere weeks

before the police killing of Charleena Lyles in Seattle, where I live and work.

I don’t know that anything could have been a more immediate example of a

situation in which police completely overstepped, used overwhelmingly excessive

force, and perhaps shouldn’t have been the first responders. She had called

them for help, and in return, they shot her seven times, which would be

excessive for almost anyone, but especially so for a woman who was shown to

have no drugs or alcohol in her system and was five months pregnant. It goes

back to the idea Ritchie explains, of historically biased perceptions of Black

women as “beasts” with superhuman strength and resilience.

Ultimately, this book submerged me in the issues of the

interactions women of color have with police, and presented fairly concrete

examples of alternatives to police responses in helping to keep women of color

safe. It made me even more acutely aware of my own privilege, and more intensely

committed to being as active an ally as possible. Put up or shut up, as they

say. Greater awareness is only the first step in a long journey.

I’ve included some links to further readings below.

And

I’ll leave with this food for thought from Ritchie: “To

strike at the root of the issue, we need to transform our responses to poverty,

violence and mental health crises in ways that center the safety and humanity

of Black women and our communities.” (231)

Further Reading

Study: Black girls viewed as ‘less innocent’ than white girls – Washington Post

Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women

Comments

Post a Comment